Excellent piece by Joel Rookwood, written following the October 2012 Everton vs Liverpool derby. Some fine points for both sides to consider

to read the full article visit http://www.joelrookwood.com/uncategorized/two-tribes-the-merseyside-derby/

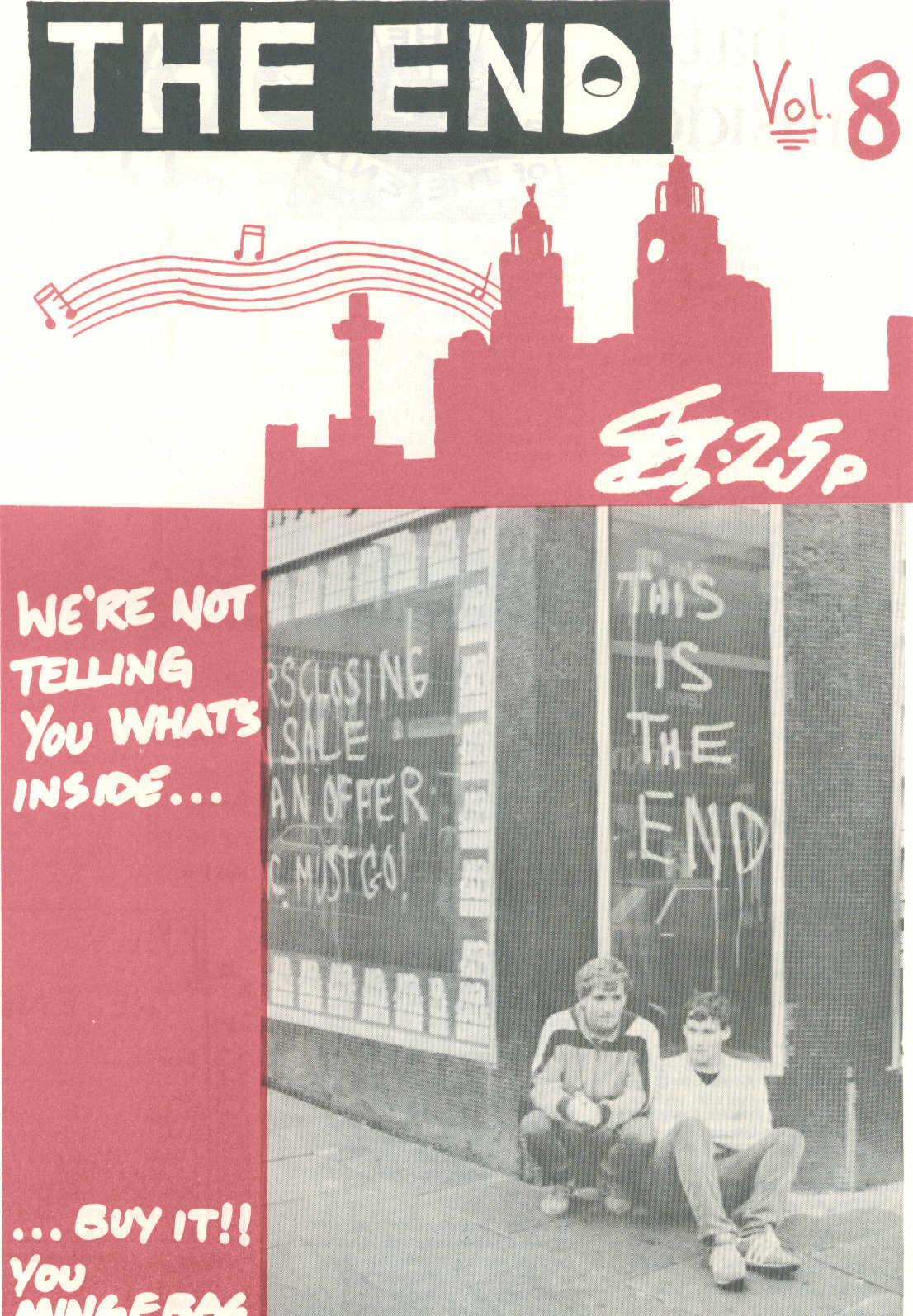

Two Tribes: The Merseyside Derby

Liverpool: a city that clings to the Mersey, drenched in historical significance – infamous for its slave trading, renowned for its political activism, popularised by its comedy, celebrated for its music, and famous for its football. A city of uncertain national standing, yet certain of itself; a worthy European Capital of Culture, in its own eyes at least. Conversely, neighbours bestow the label ‘self-pity city’, a reference to the legacy scars of troubled histories which linger below Liverpool’s surface. The depths of this misery were mined by Thatcherite conservatism: a heroine to some, heroin to others. When surviving Scousers reminisce, football is framed as an outlet, an anchor, a source of hope and pride. Two decades later, parts of the city bear only a passing resemblance to its past; yet football threatens our renovated city with decay. When the giant European Capital of Culture billboard facing Lime Street station was unveiled in 2006, proclaiming: “Red or Blue, we’re all on the same side” – my pride in this city for receiving the award veered into unfamiliar territory, where the civic unity we once took for granted now required public appeal.

A civil war is brewing on Merseyside (a place referred to by many primarily to denote a footballing umbrella). I’m not trying to overstate the city’s tribalism or the importance of football for dramatic effect; and I’m not about to legitimise borrowing from Dr King in exclaiming: ‘I have a dream that my children will one day live in a city where they will not be judged on the colour of their shirt, but the content of their character.’ If you remove text from context, all that remains is a con. In truth, rather than a synonym for war, most Scousers consider football to rank somewhere between significant and crucial. Local lives are generally consumed by additional interests, and tested by bigger challenges. Yet in our context, football is becoming increasingly divisive between followers of the city’s two teams, as attending a Merseyside derby would testify.

Most of us still consider the derby to be relatively friendly, particularly when the frame of reference is Glasgow, or Buenos Aires, or Istanbul. Yet Liverpool’s cultural wheels are in motion, travelling at a comparatively high speed. Culture is as static as language, it won’t sit still. It’s a fluid entity, shaped by conditions and experiences. Yesterday’s trainers are today’s regret and tomorrow’s resurgence. You only need to be old enough to remember Everton’s last title triumph to realise the degree and rate of change on Merseyside. ‘Friendly’ is no longer a fitting adjective. If the derby continues its descent into poisonous animosity, the venom will grow in toxicity, the antidote will prove more remote, and the determination to apply it will fade. We the people have a finite time frame in which to salvage the derby we inherited, to prevent its once ‘friendly’ nature from being consigned to history, and maybe even mythology – if as a collective, we want to.

In a time where organised social movements were alien to Scouse football fandom, a group convened to Reclaim the Kop, intent on rescuing and reinstating Kopite culture. When confronted by even more pressing issues, namely the club’s ownership, this collective evolved into Spirit of Shankly, the country’s first football supporters’ union. Faced with mediocrity, humiliation and eventually extinction, vital collective action followed. The role of SOS in helping wrestle Liverpool from the poisonous custodianship of Hicks and Gillett should not be underestimated. It led Brian Reade to dedicate his insightful account to “The Noise that refused to be dealt with.” Liverpool’s case is not an isolated one. Everton’s economic predicament could also be considered representative of a growing undercurrent of tension in English football, between the fans and various key participants in the increasingly financially-driven football ‘industry’. Evertonians have also reacted, with protests against the club’s stagnation. Although few blues would recognise let alone cite inspiration, Liverpool’s situation must have partly galvanised Everton’s response. If we want to re-direct the trajectory of our derby therefore, recent history on both sides of the park strongly suggests we can. There is a precedent for likeminded individuals producing effective collective action. It takes two to tango, but Liverpool must create half of The Noise. We might have to get the singing going too. I’ve had related conversations with lads on both sides of the divide, who seem to think I’m an idealist. Apparently we’re too entrenched in a bitter feud to rectify the damage now. A proud, football-rich city of socio-political significance, calved into red and blue, cannot recover once it has descended into enmity, I’m told.

The day before our daunting first post-Heysel trip to Juventus in 2005, my detour involved another European quarterfinal, in neighbouring Milan. AC were the globe’s finest team, Inter shuffled in their shadow. The footballing outcome of that second leg was inevitable. To my surprise however, the pre-match atmosphere lacked any tension. A Milan fan told me of the fan pact agreed around 1990 between influential parties, which halted petty violence between Inter and Milan. It wasn’t imposed by the clubs, it was an organic response from the heart of Milanese fandom – and it filtered out amongst the masses, who endorsed and upheld it. Milan v Inter is a different derby as a result. That San Siro clash is remembered for the Curva Nord flare protest, which eventually saw the game abandoned. (Their voice was heard, as Inter won the next five titles). I spent a half in each end that night amongst fans who taunted each other incessantly, but knew their limits. Despite the protest, it was the friendliest derby I have ever seen. I exited the Curva Sud to a triumphant Italian version of You’ll Never Walk Alone, dreaming of Scouse solidarity.

When former Everton director John Houlding established Liverpool FC, with a name that would have city-wide appeal, maybe then the seeds of division were sown. Yet elements of subsequent generations swapped Everton’s new home for its old on a weekly basis, before the structure of the working week and the advance of leisure time and money enabled fans to attend away games. Liverpool and Everton fans were accustomed to watching football together. There were operational interactions too: thirty-three players have played for both teams (the greatest number of transfers between Liverpool and any other club). For all Britain’s football rivalries, only eleven towns and cities have more than one team. Football enmity is typically an inter-city phenomenon in these isles. Spearheading the weighty minority, Liverpool is not a city split by postcodes like Manchester, or religion like Glasgow, or ‘success’ like parts of London. Even families contain footballing divisions – maybe that helps explain why limits have been intuitively imposed on rivalries in Liverpool, because families share experiences characterised by extremes that transcend and outweigh football. Perspective has been infused.

read more here http://www.joelrookwood.com/uncategorized/two-tribes-the-merseyside-derby/

A civil war is brewing on Merseyside (a place referred to by many primarily to denote a footballing umbrella). I’m not trying to overstate the city’s tribalism or the importance of football for dramatic effect; and I’m not about to legitimise borrowing from Dr King in exclaiming: ‘I have a dream that my children will one day live in a city where they will not be judged on the colour of their shirt, but the content of their character.’ If you remove text from context, all that remains is a con. In truth, rather than a synonym for war, most Scousers consider football to rank somewhere between significant and crucial. Local lives are generally consumed by additional interests, and tested by bigger challenges. Yet in our context, football is becoming increasingly divisive between followers of the city’s two teams, as attending a Merseyside derby would testify.

Most of us still consider the derby to be relatively friendly, particularly when the frame of reference is Glasgow, or Buenos Aires, or Istanbul. Yet Liverpool’s cultural wheels are in motion, travelling at a comparatively high speed. Culture is as static as language, it won’t sit still. It’s a fluid entity, shaped by conditions and experiences. Yesterday’s trainers are today’s regret and tomorrow’s resurgence. You only need to be old enough to remember Everton’s last title triumph to realise the degree and rate of change on Merseyside. ‘Friendly’ is no longer a fitting adjective. If the derby continues its descent into poisonous animosity, the venom will grow in toxicity, the antidote will prove more remote, and the determination to apply it will fade. We the people have a finite time frame in which to salvage the derby we inherited, to prevent its once ‘friendly’ nature from being consigned to history, and maybe even mythology – if as a collective, we want to.

In a time where organised social movements were alien to Scouse football fandom, a group convened to Reclaim the Kop, intent on rescuing and reinstating Kopite culture. When confronted by even more pressing issues, namely the club’s ownership, this collective evolved into Spirit of Shankly, the country’s first football supporters’ union. Faced with mediocrity, humiliation and eventually extinction, vital collective action followed. The role of SOS in helping wrestle Liverpool from the poisonous custodianship of Hicks and Gillett should not be underestimated. It led Brian Reade to dedicate his insightful account to “The Noise that refused to be dealt with.” Liverpool’s case is not an isolated one. Everton’s economic predicament could also be considered representative of a growing undercurrent of tension in English football, between the fans and various key participants in the increasingly financially-driven football ‘industry’. Evertonians have also reacted, with protests against the club’s stagnation. Although few blues would recognise let alone cite inspiration, Liverpool’s situation must have partly galvanised Everton’s response. If we want to re-direct the trajectory of our derby therefore, recent history on both sides of the park strongly suggests we can. There is a precedent for likeminded individuals producing effective collective action. It takes two to tango, but Liverpool must create half of The Noise. We might have to get the singing going too. I’ve had related conversations with lads on both sides of the divide, who seem to think I’m an idealist. Apparently we’re too entrenched in a bitter feud to rectify the damage now. A proud, football-rich city of socio-political significance, calved into red and blue, cannot recover once it has descended into enmity, I’m told.

The day before our daunting first post-Heysel trip to Juventus in 2005, my detour involved another European quarterfinal, in neighbouring Milan. AC were the globe’s finest team, Inter shuffled in their shadow. The footballing outcome of that second leg was inevitable. To my surprise however, the pre-match atmosphere lacked any tension. A Milan fan told me of the fan pact agreed around 1990 between influential parties, which halted petty violence between Inter and Milan. It wasn’t imposed by the clubs, it was an organic response from the heart of Milanese fandom – and it filtered out amongst the masses, who endorsed and upheld it. Milan v Inter is a different derby as a result. That San Siro clash is remembered for the Curva Nord flare protest, which eventually saw the game abandoned. (Their voice was heard, as Inter won the next five titles). I spent a half in each end that night amongst fans who taunted each other incessantly, but knew their limits. Despite the protest, it was the friendliest derby I have ever seen. I exited the Curva Sud to a triumphant Italian version of You’ll Never Walk Alone, dreaming of Scouse solidarity.

When former Everton director John Houlding established Liverpool FC, with a name that would have city-wide appeal, maybe then the seeds of division were sown. Yet elements of subsequent generations swapped Everton’s new home for its old on a weekly basis, before the structure of the working week and the advance of leisure time and money enabled fans to attend away games. Liverpool and Everton fans were accustomed to watching football together. There were operational interactions too: thirty-three players have played for both teams (the greatest number of transfers between Liverpool and any other club). For all Britain’s football rivalries, only eleven towns and cities have more than one team. Football enmity is typically an inter-city phenomenon in these isles. Spearheading the weighty minority, Liverpool is not a city split by postcodes like Manchester, or religion like Glasgow, or ‘success’ like parts of London. Even families contain footballing divisions – maybe that helps explain why limits have been intuitively imposed on rivalries in Liverpool, because families share experiences characterised by extremes that transcend and outweigh football. Perspective has been infused.

read more here http://www.joelrookwood.com/uncategorized/two-tribes-the-merseyside-derby/